If you’ve heard of Waacking, you’ve seen a piece of Punking — but not the whole picture. Waacking grew out of Punking when the style was picked up and reshaped for mainstream audiences. Over time, the name changed, and much of the deeper context — especially its gay roots — was lost

Viktor Manoel is coming to Norway in connection with Queer The W*ack (June 21 – 22) arranged by Ronald Belaza, where he will be giving a workshop, judging batttles and participating in a panel talk. On that occasion he has been interviewed by Hanne Os Wold for Dance Info Norway.

Early Life and First Sparks of Imagination

Can you tell me about your early life — where you grew up and what shaped you, especially in terms of art and creativity?

I was born in 1957 in Morelia, Mexico, and we immigrated to the United States when I was seven, I believe. I grew up in Culver City, and in Hollywood as the oldest of five.

My father, unfortunately, was an alcoholic and very abusive. But somehow, I always knew that it wasn’t him, and it wasn’t me — it was his demons. I survived him. He always played music and every Sunday, he would play Strauss, which I loved. Toward the end of his life, he became a photographer, taking pictures of Mexican cowboys. But unfortunately, his alcoholism diminished that dream.

When I was four or five, there was a radio show I loved — a superhero named Kaliman, a Tibetan hero who practiced Transcendental Meditation and all these things no one had heard about in the ’50s or ’60s. He had a villain named Count Fartok, a vampire. I remember vividly that whenever danger was near, or the vampire was about to appear, you’d hear da-da-da-daaa — Toccata and Fugue in D Minor by Bach — getting louder and louder as the threat came closer.

That’s where my imagination as an artist began. As a kid, I knew I was different – because I envisioned all of these things happening with music.

Viktor Manoel

I wouldn’t say I was an overly emotional child, but I felt a lot of the world. Later, I learned I was legally blind in my left eye — I don’t see in 3D, but I have monocular vision. When you grow up with one less sense in your body, the others get heightened. So, that’s where I think that came from, me being overwhelmed with life and the world. I often wondered, even as a kid, why no one else seemed to understand that we were destroying the world.

And then to add to the whole thing, I had asthma. So… my whole life has been based on drama that I’ve been able to turn into, I guess, art.

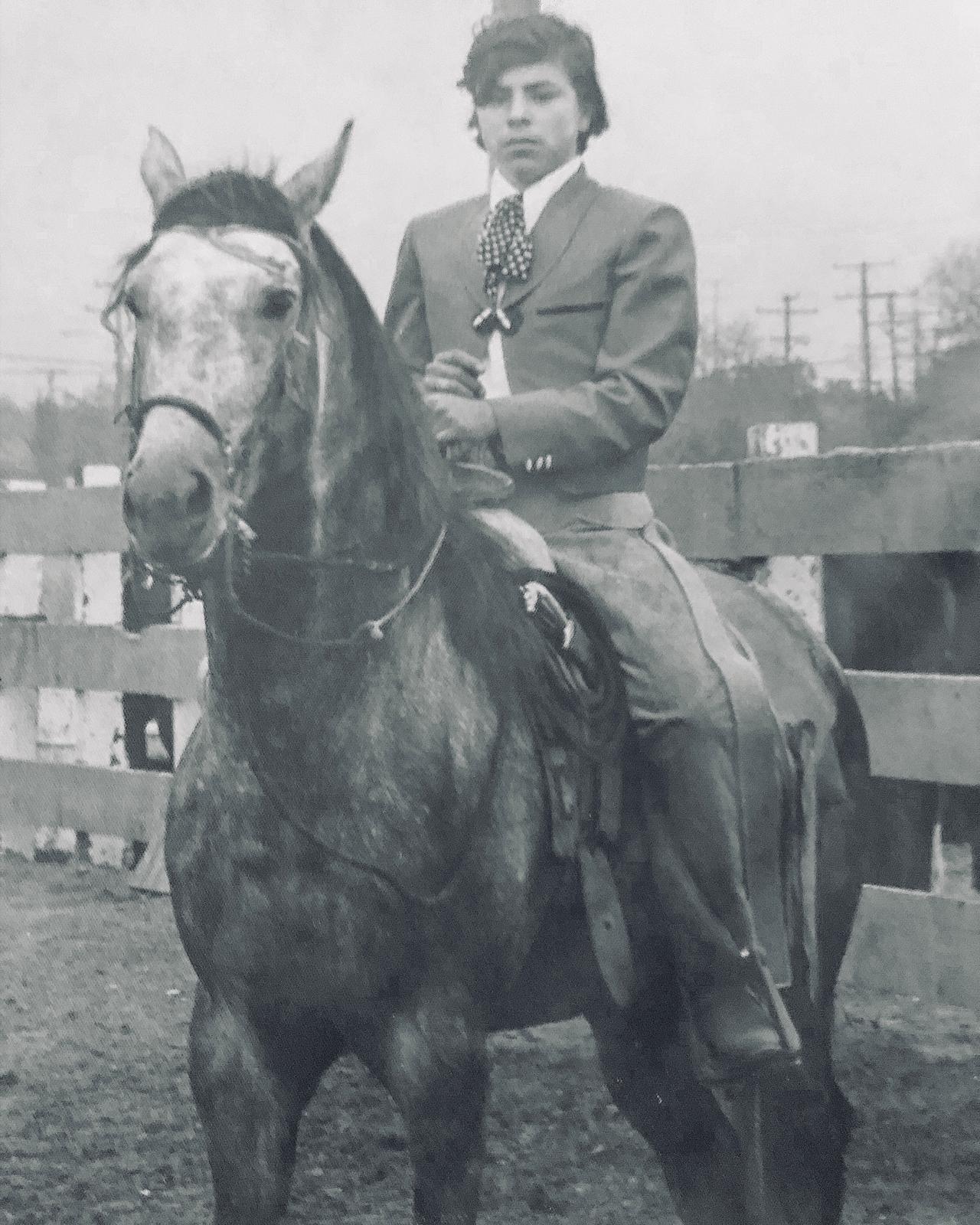

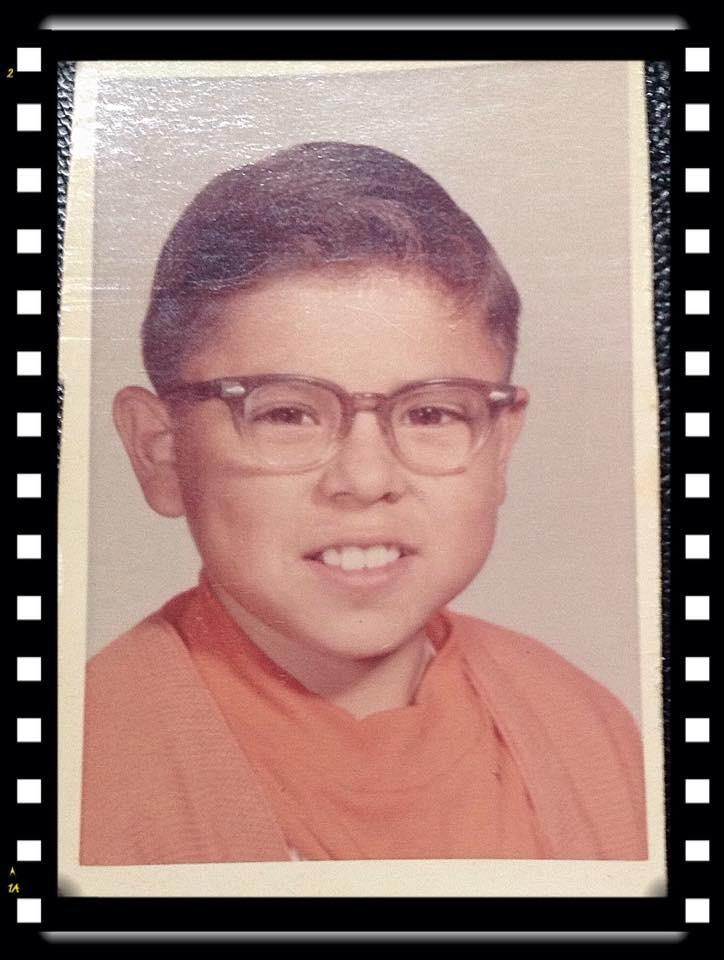

Left: Photo: Antonio Huerta (Viktor’s father) Right: school photo of Viktor Manoel.

Discovering Dance and Being ‘Different’

How did you start dancing? Was that something that came naturally to you?

Everything came natural to me, but I also had a father — like I said — that was dealing with demons, so I never wanted to showcase my talent, because I knew he would showcase me.

And understandably so. I mean, we’re a Mexican family that he brought to the United States, and I guess I would’ve been his prodigy child — but I didn’t want to be that child.

So I just stayed quiet, and did my work by myself. I knew I could paint, I knew I could draw, I knew I could do all these things…

I was also a cowboy for a while. I rode horses and bulls — because my father took pictures of them. But then I was finding out early on that I was very different.

I remember watching The Tom Jones Show in the ’60s, as a child, 10 years old, and I was like, «What’s happening to me? Like, why am I so gravitated to this man dancing?»

Not understanding. And so I would be quiet, and totally be freaking out — as a young kid, basically having a crush on Tom Jones.

Viktor Manoel

That’s when I started learning about being different — not knowing what the word was. But also understanding that in Mexican culture… it’s a crime. It’s against the law. It’s, you know — I shouldn’t exist.

And then watching things around me, where people were being ostracized horribly for being what I was feeling I was becoming.

So I had to learn how to navigate life in a world where I was not wanted.

Did you at some point find a space where it was safe to express who you were?

No, I created it. I would create my spaces. Sometimes people talk about watching television and not being represented, I never thought about that. I was never angry about not being represented, I just represented myself.

Creating Punking in the Clubs of 1970s LA

How would you describe the environment and circumstances that led to the creation of punking?

We didn’t create anything — that’s the thing. We were just acting out, just behaving, playing. Taking vignettes from movies, doing our own thing in the club. We were just trying to have fun.

It wasn’t a club dance, because no one else was doing it except us. It wasn’t a social dance either — it was not done socially. It was an urban dance, because we were urban kids living in urban areas. We weren’t street kids. We were gay kids — or gay adults — going into a club to express ourselves, to play tag, to laugh, to have a good time. We just happened to put music to it.

The main person of this dance was Andrew Frank. There was also Arthur Goff — I think he was from the Virgin Islands — Billy Starr Estrada, who was Chicano, and China Doll — Kenny, who was Chinese and got his nickname because he looked like a china doll. There was Lonny Carbajal, who was Filipino. Michael Angelo Harris, half-Japanese, was the Svengali of the dance. He gave us the heartbeat — the music.

They knew me as Manoel — not Viktor. That’s how it is in Latin culture; people call you by your middle name. There was also Tinker Toy — he was black. Tommy Mitchell was black too. And me, I was Mexican. We were multicultural kids.

I remember seeing them in the club for the first time in 1975. I was mortified. It was my first time in a gay club, and I knew — back then, you could get arrested just for being there. I grew up in the projects, so I was already used to living a life of caution. But I found a safe haven in dancing.

Before that, I’d done folk dancing. I got into it after a fight with my father — he sold my horse to punish me. So I got into Mexican folk dancing just to piss him off. He hated it. That was my way — always pushing against whatever tried to box me in.

I was a kid with glasses, a patch over one eye and I was always fighting my way through things.

Viktor Manoel

I knew that I couldn’t do it in a harsh way, because then I would not exist. So I navigated my own narrative and that’s when I found my friends in the ’70s. That’s how this dance came to be.

At first, it didn’t have a name. We were just posing, like they did on the East Coast. But then we called it Punking. «Punk» was a slur — «you’re nothing but a punk, you’re a low life, you’re a faggot». It came from when Andrew had tried to visit his husband in jail, and Michael Angelotold him, «You’re nothing but his bitch — you’re nothing but his punk.» We took that word and flipped it. We said, «We’re punks. We’re punking.» The idea was to dominate the music — make it our bitch. The way you would make someone your bitch in jail.

So none of this has pretty history. It wasn’t pretty times. I didn’t even know where they lived, we just gathered in a club. To this day, they’re all gone — they all died.

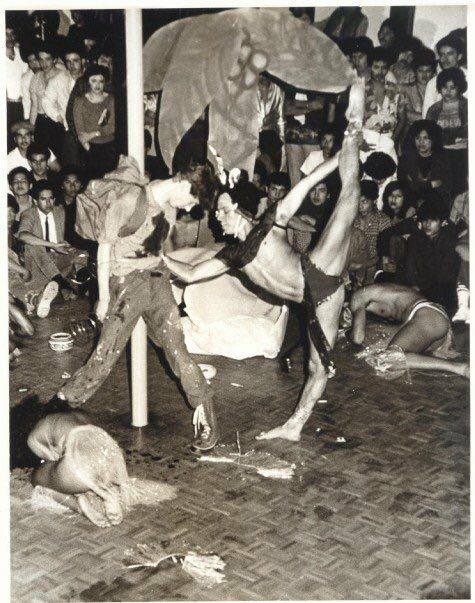

Left: Viktor doing Mexican folk dance. «I was Mexican and I did the deer dance. So that’s how I did my posing, like a deer» Photo: Antonio Huerta (Viktor’s father) Right: Viktor (doing the splits) winning a dance competition at Gino’s II in the late 70’s.

What inspired you? What was the common language that shaped punking — and what music did you dance to?

The music wasn’t at all what we were using. Whatever the music at the time was, which was disco, had nothing to do with the style. That’s something that got added on later through what I call the franchise. What you all know now is the polished, packaged version — a business. But Punking, at its core, still stands for what the word punk means: anarchy. You can’t put it in a box.

The music we used came from Michael Angelo — he picked the sound. It was funk, sped-up funk: Papa Was a Rolling Stone, Shaft, Prince — «Just as Long as We’re Together», Quartz. Anything with that funky, plucking bass line and sharp staccato. It became our soundtrack.

We also shared a love for old Hollywood. Sunset Boulevard — a story about a silent film star. We loved Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford. There’s a book called Four Fabulous Faces by Larry Carr — we used it as a Bible for photography. We’d take those photographs and turn them into poses, into movement.

We were inspired by silent films — the jump cuts, the strobe-like rhythm of it.

Viktor Manoel

We loved Erté, the first Art Deco artist, and the Ballets Russes. Julie Newmar in Li’l Abner, her character Stupefyin’ Jones — incredible poses. Or Eric Von Zipper in How to Stuff a Wild Bikini — there was this Himalayan touch moment where someone would freeze on contact. It was all games. We made it up as we went along.

Everyone brought something unique to the style. Lonnie was a gymnast — he loved Nadia Comăneci. Tinker loved Bugs Bunny and brought cartoonish exaggeration into his movement. I was Mexican — I moved my arms like a cowboy, like I was roping cattle or doing the deer dance from folk traditions. Michelangelo was Japanese — he brought kabuki-inspired gestures. And Andrew, the alpha of the group, was a cheerleader in high school — he brought in this foot-stomping when he danced.

What’s funny is now, people take one movement — like Tinker’s arm movement that he got from Bruce Lee and nunchucks — and turn it into a whole style (Waacking). That’s not how it was. One of the elements, whacking, with an «h,» came from the Batman TV show. You know — «POW!» «BAM!» «WHACK!». Comic book hits. «Whack» meant to strike with force. That’s how we moved.

Nothing we did was invented from scratch. We stole from everything.

Viktor Manoel

A collage of some of the visual references mentioned by Viktor: the ‘Whack!’ graphic from the 1960s Batman TV series, Bugs Bunny’s exaggerated cartoon style, Julie Newmar as Stupefyin’ Jones in Li’l Abner, and a scene from Sunset Boulevard.

When Punking Was Noticed (But Never Named)

At the time, did you have a sense that people were starting to take notice of what you were doing — for example within the industry?

No, not really. I mean, the industry took it because they would see it. But we had no sense of that at the time, we didn’t care. We were doing it for ourselves, for fun.

But then we started working — my friends danced for Diana Ross and me and Tommy worked with Grace Jones. So yeah, it started to be seen — in gay culture, in gay clubs, and in performances in places like Las Vegas.

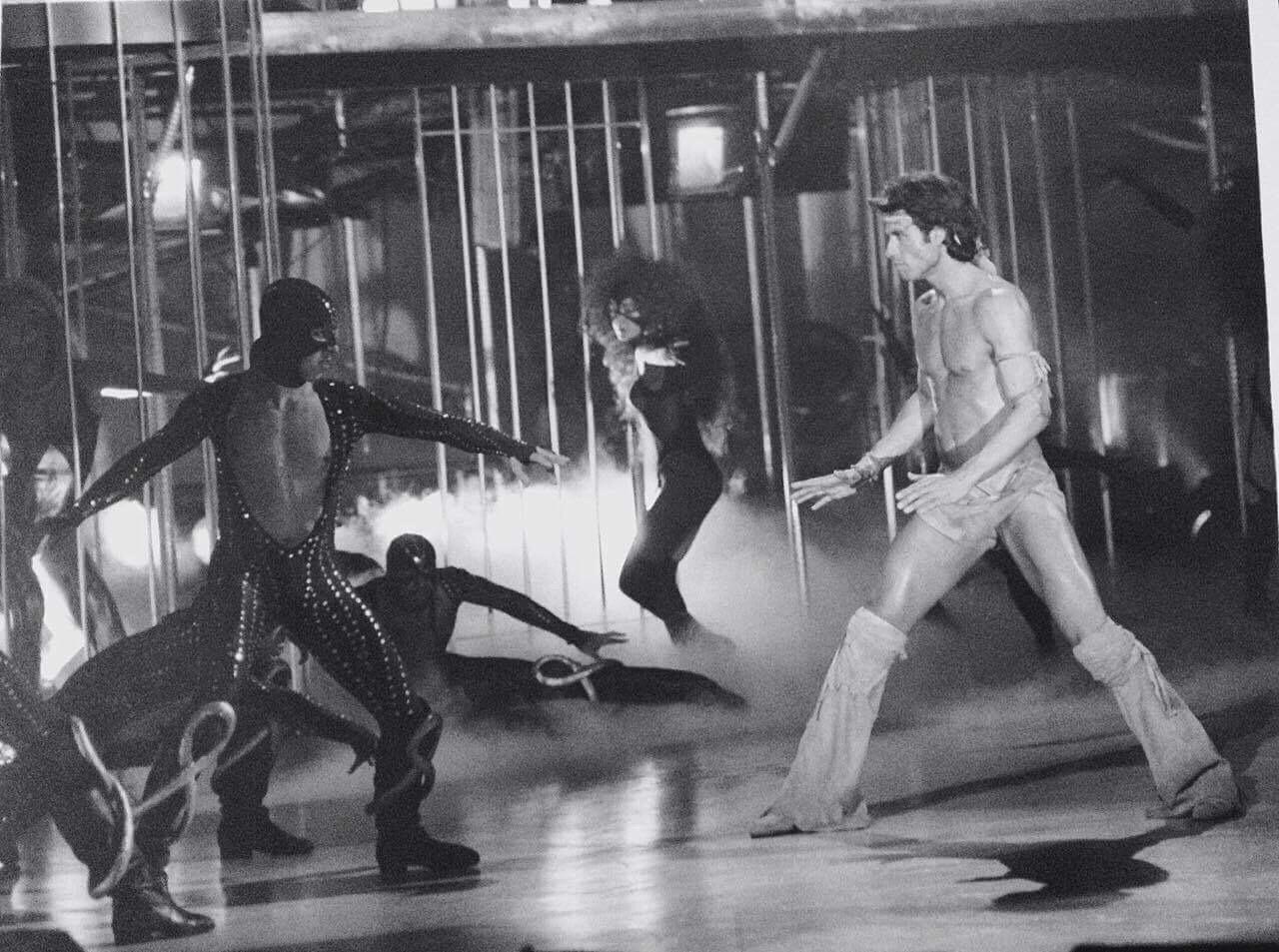

Then came things like the TV show Solid Gold, where people started mimicking the posing — it started to spread. John Travolta even tried to do it in Staying Alive, but he did it so poorly we called it the «shampoo dance.» Ironically, I was actually in that film as one of the lead dancers — part of a dance that was becoming mainstream. I couldn’t say what it really was, or where it came from, because we were gay. At that time, you couldn’t say that.

That was also the first time I heard about what would become the AIDS crisis. Some dancers from New York were extras, and they warned us: «Something’s happening in New York… and it’s killing us.» It didn’t even have a name yet.

And here I am, in a movie called Staying Alive… learning about a disease that’s killing us.

Viktor Manoel

My life has always had that contrast — positive and negative — side by side.

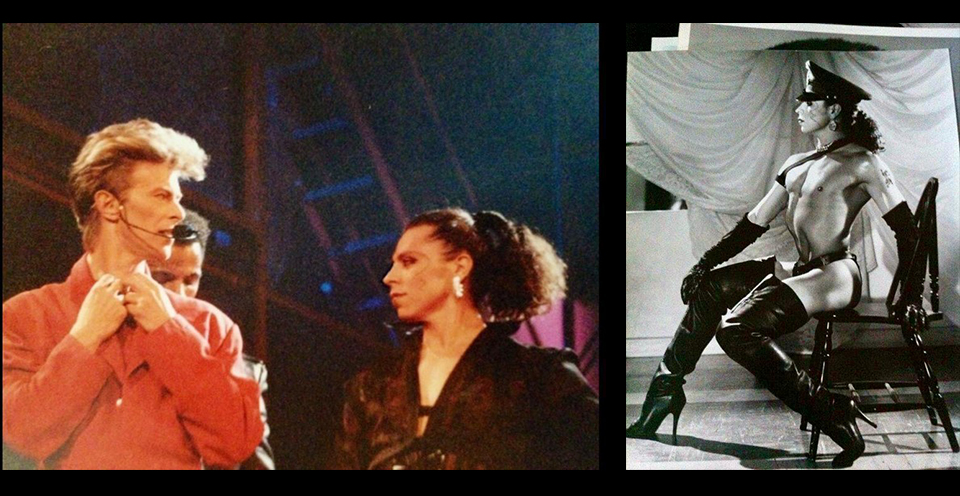

Later, I was on Star Search, which became huge in the ’80s and ’90s. Beyonce, Britney — so many people got discovered there. I did the pilot. During the day, I was doing jazz and technical dancing. At night, I was performing in a lesbian bar and becoming more androgynous — I started growing my hair. That show at night is what eventually led to David Bowie. Five years later, I was on tour with him.

When I got the call for Bowie, I finally understood: those five years of doing these underground shows, wondering «why am I doing this?» — they were preparation. I was becoming gender savage. That same weekend, I had an audition for Madonna’s Who’s That Girl tour. I told her team I couldn’t do it — David had called first.

After I had auditioned for them I had gone to church and said: «God, it’s in your hands. Whoever calls me first, that’s who I’ll go with.»

So 1987 — turning 30 — was a rollercoaster. My career was exploding, but privately, my life was falling apart. My friends were dying and I had to walk onstage and represent this beautiful creature.

When I came back from that tour, I didn’t want to do it anymore. It was too much for my mental health.

Grief Became Discipline

How did the AIDS crisis affect your relationship to dance and how you expressed yourself?

It affected me in the sense that if I could use it, I would — but if I couldn’t, I’d shut off and just do my job.

David Bowie — may he rest in peace — was incredible to me on tour. Like a big brother.

Viktor Manoel

He was always aware of the state of the world. In Rotterdam, he asked to speak with me. «Can I talk to you?» he said. He wanted to talk about AIDS. I said, «Yeah, I know what’s happening.» He apologized — «I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to offend you» — but I told him, «No, it’s fine. I’m very aware of it. Thank you.»

I don’t shit where I eat. I was never going to use my status on stage to get laid — I mean, I’m a man, sure, but deep down, in my artistic heart, I’m actually pretty prude.

Back when bathhouses were popular, I’d go sometimes — but it never sat right with me. Some of my friends, may they rest in peace, used to tease me: “What, you think you’re Cinderella waiting for Prince Charming?” Because I’d be like, «I don’t even know their names — who are these people?»

It sounds funny, but it came from something deeper. Even early on, I understood that as a gay boy, I’d have to figure out if I was going to be used or loved. And love — well, that didn’t seem to be in the cards for me. I was a good-looking boy, so I told myself, Fine, if I’m going to be used, at least I’ll enjoy it. But I still had to protect my heart.

I remember sitting in a bathhouse once thinking, «This is like a candy store. And when you eat too much candy, you get cavities. This is not right.» That’s when I shifted focus to dancing. Dance, dance, dance, nonstop. I danced 24/7 for a year and a half — and that’s when my career really took off.

I was also angry. Angry at the world. But instead of turning that into violence — martial arts, fighting — I put it into technique. Because otherwise, I might have hurt someone… or ended up in jail. So I put it all into dance.

That rage, that fire — it’s what opened up my dance career. It became a way of expressing pain, not just performing.

My art is savage. My art is gender savage.

Viktor Manoel

Me, personally? I’m quiet. I separate performance from real life. I used to say: this is me onstage, but offstage, I’m alone, resting, watching nature.

David saw that in me. On the Glass Spider tour, he gave each dancer a spoken line in the intro to «Up the Hill Backwards.» Everyone else had these dramatic monologues. Mine was just: «You’re just not educated properly.» And I walk away. That’s all he had me say — because he loved the fact that I was always educating myself on how to live authentically. He told me, «Viktor, never become a cartoon or a caricature of your talent. Never take art and business personally. Know when to walk in, and when to walk out.»

He was always generous with his words. Once, in Minneapolis, Prince threw a party for the Bowie tour. I didn’t want to go — my family was asking me for money, everyone wanted something from me, and I just wanted to be left alone. But David insisted. So I went.

Everyone rushed into the party room, but I stayed by myself. Then I felt someone watching me — I turned around, and it was Prince. He was wearing a suit covered in hearts. I introduced myself, and he said, «Oh, I know who you are. I’ve been watching you on tour.» We talked music — I told him I used to dance to his early stuff but when he got into The Ladder, he lost me. He asked, «Are you going to join the party?» I said yes. He thanked me for coming.

Later, David came up to me and said, «Did you hear what one of the band members said?» I hadn’t. He told me, «They said that if you don’t kiss Prince’s ass — like say good morning or flatter him — he’ll dock your pay.» I said, «So?» David laughed and said, «If I did that to you, you’d have no money.»

That’s the kind of dancer I was. I wasn’t there to socialize or to kiss ass.

Viktor Manoel

I probably don’t like your music, I’m here to do my job.

It goes back to my father. If he found out I had talent, he’d try to use me to profit. I’m not stupid, I know it’s a business — and I choose when and where to sell.

Punking and the 2000s Revival

How did you experience what some now call the resurgence of Waacking that happened in the early 2000s?

I wasn’t brought back until 2009. It was Tony Basil who brought me back, she called me in December 2009. There were two other people at the meeting — I won’t mention their names because they’re not important to this part of the story — but they validated who I was and asked me questions: What came first? What clubs did we go to? How did it all start?

Then they showed me videos of what was happening at that time, and said, «You need to come back. They’re trying to change history.»

So I did. I sat down and told them about everything: the clubs, the addresses, how we met, what we did, why we did it — everything I’ve been telling you. That’s how I re-entered the conversation.

Now, when I first heard the term «Waacking» with a double ‘a,’ I was like, What is that? I was told someone used it in a magazine in Japan. To me, it seemed like they heard the word «whack» but didn’t know where it came from. Maybe they looked it up and saw «wack» spelled W-A-C-K — which means fake or not legit — and figured that couldn’t be right, so they just added an «a.» But «waack» with a double «a» has no meaning in the dictionary. So, to me, that’s made up.

What really bothered me, though, was how people started using my words, my history — and tacking it onto their version of the dance. Even today, I hear people say «Waacking is an LGBTQIA dance from the 1970s.» But that’s impossible. Because the term LGBTQ didn’t exist in the ’70s — it came later, in the ’80s. The same goes for calling it a «queer» dance from the ’70s. The word «queer» didn’t come in until the late 80’s. It wasn’t «queer,» it wasn’t «LGBTQIA+.» It was a gay culture dance. We were friends of Dorothy.*

So when I came back into the scene, I said: This is your mess. I know who I am. I know what we were. And I teach that — from the beginning to where it’s evolved now. I don’t have a problem with the AA scene or anyone dancing the style — until they start claiming my part of the history without naming the people who created it with me.

I am their voice. They can’t speak anymore. I’m not doing this for me. I’m here because I have no choice.

Viktor Manoel

Even when students come to me from the AA scene, I tell them: What you’ve learned isn’t all wrong. But I’m going to show you how to connect it to the truth, I’m going to give you glue.

And I think that’s why some people have a problem with me — because I don’t dismiss people, unless they cross the line into falsifying history. That’s when I get angry. Because what about my friends? You don’t even know their names, or how they died. You don’t know this month is hard for me because they’re all gone — AIDS took them. I’ve lost over 500 people.

So I have to be careful not to get bitter. I don’t want to be a bitter old man. This dance wasn’t bitter. This dance was fun. There was no drills, it was just a party — a way to have a good time. And it became something big.

*»Friends of Dorothy» is a historical code phrase used to refer to gay men, originating from the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz and its iconic star, Judy Garland.

Viktor Manoel doing a judge showcase at Streetstar International Streetdance Festival in Stockholm in 2015.

Don’t Use My Name to Prove a Point

It felt like something shifted during the COVID pandemic — like there was more interest in Punking’s roots, and people were more open to learning about its origins. Did you feel that shift?

Yeah, because I was part of it.

I was teaching — someone reached out to me during the pandemic, Julia Cheng. She contacted me and said, «Hey Viktor, have you ever done zoom?» I said, «What’s that?» She explained, «Oh, I’ll hook you up.» She got a grant and studied with me for about a month during the pandemic.

Honestly, the pandemic was the best thing that ever happened — for me personally, not for what it was. Because I didn’t have to deal with people.

I like being by myself. I’ve already survived one pandemic, this was nothing.

Viktor Manoel

The only thing that made it difficult was that my 93-year-old mother was living with me, and my brother, who’s HIV-positive and had cancer, was living with me too. That was the real worry — how to keep them safe. And how to live, because suddenly the world shut down. But I found a way.

Yes, people were more curious during that time. But honestly, I think they were forced into it. Because when you’re forced into isolation, you find ways of staying healthy. So in that way, it was done from a healthy point of view, I think.

But then people started getting righteous about it — like knowing the history would somehow make them more talented. But that’s not how it works. If you don’t have rhythm, knowing the history won’t give you rhythm. So I always ask people: Why do you really want to know this?

And I tell them: Don’t use my name to prove a point. Don’t drag me into a debate about what’s «right» or «wrong.» My friends — the people who created this with me — they don’t deserve that. Don’t politicize it.

Because here’s how I feel: the truth doesn’t need to be defended. It is what it is. There’s no duality here. People ask, «Well, can we allow space for both perspectives?» Hell to the no. This is what it was. And I’m sorry if that makes you uncomfortable — but we survived it.

If you’re uncomfortable with our history, that’s something you need to sit with. People are so scared of uncomfortable conversations. Everyone’s like, «Let’s not rock the boat.»

I say fuck that.

Viktor Manoel performing at B-Side Hip-Hop Festival 2025 in Birmingham, in a veil in acknowledgement of his friends. «I consider myself as a kind of widow of my art — I’m here to represent the dead.» «Photo Sniped by KIM».

If It Hurts, Start Creating Happy Memories

What is it like for you now, traveling the world and teaching this dance that you and your friends created?

It’s gotten easier over the past 15 years of doing this. Emma Jayne Park, who I’m here with in Scotland, took my class over a decade ago. She once told me, «If it hurts, start creating happy memories.» So now, I take the memories of dancing with my friends who are no longer here — and I recreate that energy in the classroom. That’s what I do.

This year feels especially significant. It’s the first time I’ve been able to travel for this long — the whole month of June — teaching in different places. The last time I was in Europe during June was for the Glass Spider Tour with David Bowie, when all my friends were dying. The last time I was in Scotland, London, Gothenburg — all those places — it was with him. And now it’s Pride Month. So it feels like not just recovering ashes, but rebuilding from them.

Back then, I had to perform like nothing was wrong. I looked glamorous on stage, but backstage I was locking myself in my hotel room, trying to hold it together. Now, every day I’m grateful that I’m mentally strong enough to be here. Even yesterday — I arrived from London on an early train, walked miles because of a bike race that shut down the streets, carried my suitcase up five flights because the elevator was broken, grabbed a quick soup, showered, and went straight to class. It was freezing, I was exhausted — and still, I had to walk into the event and be present.

People were excited — «Oh my God, he’s here!» — and I had to ground myself. I’m learning to find a balance between letting others have their moment and allowing myself to read the room, feel the energy, and adapt to it.

I have a structure for how I teach, but within that, I adjust based on what I sense from the group.

Viktor Manoel

For example, this morning I learned something about two students I had been feeling something from but couldn’t quite place. After class, they thanked me. And I realized, that’s what I was picking up on. That’s why I teach the way I do — it’s more than steps; it’s an experience. As Alyssa Briteramos in Sweden says, «Taking Viktor’s class is an experience.»

I’m helping others heal because I’ve survived.

Yesterday in class, a young gay girl came up to me and said she fears for her life. I told her, «Don’t be afraid. You’re going to be okay. We survived for you. Whether you’re doing it right or wrong, you’ll survive. Don’t ever be afraid.»

You know, people are afraid of what’s going to happen. I really believe we’re living through a time of necessary renewal. If you’re into astrology, Pluto was last in Aquarius in 1776 — and you can look up what was happening then. A lot of upheaval. And here we are again.

I believe in Christ, I’ve been to Israel, walked those paths, and I’ve been to Rome. But I also believe in astrology, in meditation — in anything that brings me back to the gift of my talent. I see that as a gift from faith. And I know I can’t keep it to myself anymore.

I’m not saying I’m forced to be out in the world. But I am being called out into it.

Punking Belongs to Everyone

Is there anything we haven’t covered that feels important for you to share?

Yeah. I just want people to know that Punking now belongs to everyone — LGBTQIA+, straight, queer, whoever. I’m not here to exclude anyone.

There’s no pecking order in what I teach. No hierarchy. It’s not a franchise, and it’s not a business — even though, yes, we sometimes have to operate within those systems. I tell my students: if you’re going to step into that cage — that competition world — just know why you’re there. Don’t expect anything except to showcase your talent.

And I say to them, «If you’re trying to win — good luck.» Because those systems are already set in their ways. But I guarantee you: if you go in there as yourself, with Punking, they’ll never forget you. That’s how it started. People didn’t forget us. We weren’t trying to make a statement — we were just having fucking fun. And we need to get back to that.

Now Punking is done socially. Now it’s seen as a queer dance. Now straight people do it too. It belongs to everyone. It’s become a kind of personal anarchy — a rebellion against rigidity. If you punk your life every single day, you’re going to be okay.

When my students call me in crisis, I tell them,

«Just punk the day. Why are you making it so hard?» It’s not heart surgery — thank God. Art isn’t heart surgery.

Viktor Manoel

I’ve never known art to grow from a place of joy. Sure, you can paint flowers — but you can also paint flowers from grief. You can express beauty from the ugly. You can vomit your art. You can turn your pain into something meaningful.

Put a soundtrack on it. Music doesn’t even have to match your feelings. Just hit play, move your body, record it, and you’ll be surprised: Oh… I didn’t know I could do that.

That’s what Punking is. It has no boundaries. The only structure it has is the structure of emotion — because our feelings do have shape. Beyond that, it’s just color to splash, energy to release, however you want.

Punking is an art form. It’s a way of living. That’s how I’ve lived: I live art, and I love life. Even when I don’t like life, I still love living it.

I’m blessed to still be here. Art is how I’ve survived. Simple as that.

Viktor Manoel

Viktor Manoel (born 1957) is a Mexican–American dancer, choreographer, writer, and actor.

He has worked with choreographers such as Édouard Lock of Canadian dance group La La La Human Steps and Toni Basil. Basil hired him for David Bowie’s world stadium Glass Spider Tour after she spotted him performing in a LA nightclub in 1987.

Manoel has performed in numerous shows including Open Doors and Whistle Revisited (based on Stephen Sondheim’s Anyone Can Whistle), as well as with Grace Jones, and Canadian singer Norman Iceberg.

He has also appeared in film such as Staying Alive (1983) directed by Sylvester Stallone, Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo (1984), Glass Spider (1988) directed by David Mallet, and Female Perversions (1997) directed by Susan Streitfeld.

As a cyclist, Manoel has raised significant funds for many organizations taking part in different AIDS rides and marathons of various distances across North America each year

Hanne Os Wold is a multidisciplinary artist whose work spans dance, choreography, acting, writing, and teaching. In her praxis, she merges her street and club dance background with contemporary performance, constantly exploring and evolving her artistic expression.

Punking/w*acking in Norway

In 2024, Ronald Belaza and Ida Louise Sundby were ambassadors for the Day of Dance in Norway with the dance style punking/w*acking, and here you can read more about them and the dance style.

Article about Punking/Whacking/Waacking. Would you like to get to know and delve more into the history of the Punking/Whacking/Waacking style? Then we recommend reading the article by Alyssa Briteramos: «Punking: How appropriation revitalized it and the role institutions play in the protection and longevity of this elusive art». It was published in Nordic Journal of Dance (Volume 14(2) 2023), and can be read here (page 22).